- Home

- Christiane Northrup

The Wisdom of Menopause Page 2

The Wisdom of Menopause Read online

Page 2

Little did I know that these bursts of irritability over petty family dynamics were the first faint knocks on the door marked Menopausal Wisdom, signaling that I needed to renegotiate some of my habitual relationship patterns. Nor did I know that by the time I began to actually skip periods and experience hot flashes, my life as I had known it for the previous quarter century would be on the threshold of total transformation. As my cyclic nature rewired itself, I put all my significant relationships under a microscope, began to heal the unfinished business from my past, experienced the first pangs of the empty nest, and established an entirely new and exciting relationship with my creativity and vocation.

All of the changes I was about to undergo were spurred, supported, and encouraged by the complex and intricate brain and body changes that are an unheralded—but inevitable and often overwhelming—part of the menopausal transition. There is much, much more to this midlife transformation than “raging hormones.” Research into the physiological changes taking place in the perimenopausal woman is revealing that, in addition to the hormonal shift that means an end to childbearing, our bodies—and, specifically, our nervous systems—are being, quite literally, rewired. It’s as simple as this: our brains are changing. A woman’s thoughts, her ability to focus, and the amount of fuel going to the intuitive centers in the temporal lobes of her brain all are plugged into, and affected by, the circuits being rewired. After working with thousands of women who have gone through this process, as well as experiencing it myself, I can say with great assurance that menopause is an exciting developmental stage—one that, when participated in consciously, holds enormous promise for transforming and healing our bodies, minds, and spirits at the deepest levels.

As a woman in midlife today, I am part of a growing population that is an unprecedented 48.5 million strong in the United States alone. This group is no longer invisible and silent, but a force to be reckoned with—educated, vocal, sophisticated in our knowledge of medical science, and determined to take control of our own health. Think about it: more than 48 million women, all undergoing the same sort of circuitry update at the same time. By virtue of our sheer numbers, as well as our social and economic influence, we are powerful—and potentially dangerous to any institution built upon the status quo. Baby boom women (those born between 1946 and 1964) are now the most affluent and influential group in the world. It’s clear that the world is changing, willingly or otherwise, right along with us. And in many instances, it’s changing for the better.

It’s no accident that the current movement of psychospiritual healing is composed largely of women in their thirties, forties, fifties, and sixties. We are awakening en masse and beginning to deliver a much-needed message of health, hope, and healing to the world.

My personal experience, now shared by millions of others, tells me that the perimenopausal lifting of the hormonal veil—the monthly cycle of reproductive hormones that tends to keep us focused on the needs and feelings of others—can be both liberating and unsettling. The midlife rate of marital separation, divorce, and vocational change confirms this. I, for one, had always envisioned myself married to the same man for life, the two of us growing old together. This ideal had always been one of my most cherished dreams. At midlife I, like thousands of others, had to give up my fantasies of how I thought my life would be. I had to face, head-on, the old adage about how hard it is to lose what you never really had. It means giving up all your illusions, and it is very difficult. But for me the issue was larger than where and with whom I would grow old. It was a warning, coming from deep within my spirit, that said, “Grow … or die.” Those were my choices. I chose to grow.

MIDLIFE: REDEFINING CREATIVITY AND HOME

For most women, identity and self-esteem are generated by our associations and relationships. This is true even for women who hold high-powered jobs and for women who have chosen not to marry. Men, by contrast, usually get most of their identity and self-esteem from the outer world—the job, the income, the accomplishments, the accolades. For both genders, this pattern often changes at midlife.

Women begin to direct more of their energies toward the world outside of home and family, which may suddenly appear as a great, inviting, untapped resource for exploration, creative expression, and self-esteem. Meanwhile, men of the same age—who may be under-going a midlife crisis of their own—are often feeling world-weary; they’re ready to retire, curl up, and escape the battles of the workplace. They may feel their priorities shifting inward, toward home, hearth, and family.

It’s an ironic transposition: the man is beginning to look to relationships for his “juice”; the woman is feeling biologically primed to explore the outer world. In married couples, this often produces profound role shifts. In the best of all worlds, the man retires or cuts back on work, becoming the chief cook and bottle washer at home, and providing emotional and practical support for his wife’s new interests. She, in turn, goes out into the world to start a business, get an education, or do whatever her heart dictates. If their relationship is adaptable and resilient, they adjust to their new roles. Some are so energized by their newfound freedom and passion that they fall in love all over again. If a woman’s partner is not willing to grow, however, he (or she) may become jealous of her success and independence, and put pressure on her to continue to care for him as she has always done. He may even get physically sick, often in the form of heart disease and/or clinically dangerous high blood pressure. It’s important to note that this is not a conscious or willful act; he’s simply responding to the promptings of our lopsided culture.

A woman often finds herself in the difficult position, then, of having to choose between returning to the role of caretaker to nurture her husband at the expense of her own needs and pursuing her own creative passions. It’s an old story, common to women in many cultures, not just our own. The woman in menopause, who is becoming the queen of herself, finds herself at a crossroads of life, torn between the old way she has always known and a new way she has just begun to dream of. A voice from the old way (in many cases it’s her husband’s voice) begs her to stay in place—“Grow old with me, the best is yet to be.” But from the new path another voice beckons, imploring her to explore aspects of herself that have been dormant during her years of caring for others and focusing on their needs. She’s preparing to give birth to herself, and as many women already know, the birth process cannot be halted without consequences.

Caring for others and pursuing unexplored personal passions are not necessarily mutually exclusive choices, but our culture makes them seem so, always supporting the former at the expense of the latter. This is part of what makes the midlife transformation so much of a challenge—as I know only too well.

BLAZING A NEW TRAIL

Throughout most of human history, the vast majority of women died before menopause. The average life expectancy for a woman in 1900 was only forty. For those who survived, menopause was experienced as a signpost of an imminent and inevitable physical decline. But today, with a woman’s life expectancy at eighty-four years, it is reasonable to expect that she will not only live thirty to forty years beyond menopause, but be vibrant, sharp, and influential as well. The menopause you will experience is not your mother’s (or grandmother’s) menopause.

Here’s the truth: most Americans don’t get old at age sixty-five, either physically or mentally. The groundbreaking research of Lydia Bronte, Ph.D., former director of the Aging Society Project (funded by the Carnegie Corporation) and author of The Longevity Factor (HarperCollins, 1993), reveals that many people will have three different careers over their life span. Bronte says they’ll likely have their first career in their thirties and forties, another in their fifties and early sixties, and still another in their seventies. Almost half of the people who Dr. Bronte studied had a major peak of creativity beginning at about age fifty and, in many cases, lasting for twenty-five to thirty years. That means that the new middle age is from fifty to eighty!

Women of

the World War II generation, in contrast, whose female role models tended to be like June Cleaver on Leave It to Beaver, had an entirely different social and political environment in which to make their transition. Menopause (like menstruation, for that matter) was not discussed in public. Today this is no longer true. As we break this silence we are also breaking cultural barriers, so that we can enter this new life phase with eyes wide open—in the company of more than 48 million kinswomen, all undergoing the same transformation at the same time. And, as you’ll soon discover, the changes taking place in midlife women are akin to the power plant on a high-speed train, whisking the evolution of our entire society along on fast-forward, to places that have yet to be mapped. Whether you climb aboard this fast-moving train or step aside and let it pass will play a major role in how far you go and how you feel along the way.

Ultimately, I’ve found this journey bracing, exciting, and health-enhancing. And I’m certainly not alone. A 1998 Gallup survey, presented at the annual meeting of the North American Menopause Society, showed that more than half of American women between the ages of fifty and sixty-five felt happiest and most fulfilled at this stage of life. Compared to when they were in their twenties, thirties, and forties, they felt their lives had improved in many ways, including family life, interests, friendships, and their relationship with their spouse or partner. In other words, the conventional view of menopause as a scary transition heralding “the beginning of the end” couldn’t be further from the truth.

When I wrote the first edition of this book back in 2001, I truly wanted to believe that statement. I had faith in it, even though my heart was broken and the life I had known for twenty-five years was dying. Now, ten years later, I see how clearly every moment of that perimenopausal labor pain was a necessary part of my rebirth into the happy, healthy, fulfilled woman I have become today.

So no matter what is happening in your life right now, take heart. Please join me—and the millions of others who have come before and will come after—as we transform and improve our lives, and ultimately our culture, through understanding, applying, and living the wisdom—and joy—of menopause and beyond.

1

Menopause Puts Your Life

Under a Microscope

It is no secret that relationship crises are a common side effect of menopause. Usually this is attributed to the crazy-making effects of the hormonal shifts occurring in a woman’s body at this time of transition. What is rarely acknowledged or understood is that as these hormone-driven changes affect the brain, they give a woman a sharper eye for inequity and injustice, and a voice that insists on speaking up about them. In other words, they uncover hidden wisdom—and the courage to voice it. As the vision-obscuring veil created by the hormones of reproduction begins to lift, a woman’s youthful fire and spirit are often rekindled, together with long-sublimated desires and creative drives. Midlife fuels those drives with a volcanic energy that demands an outlet.

If it does not find an outlet—if the woman remains silent for the sake of keeping the peace at home or work, or if she holds herself back from pursuing her creative urges and desires—the result is equivalent to plugging the vent on a pressure cooker: something has to give. Very often what gives is the woman’s health, and the result will be one or more of the “big three” diseases of postmenopausal women: heart disease, depression, and breast cancer. On the other hand, for those of us who choose to honor the body’s wisdom and to express what lies within us, it’s a good idea to get ready for some boat rocking, which may put long-established relationships in upheaval. Marriage is not immune to this effect.

“NOT ME, MY MARRIAGE IS FINE”

Every marriage or partnership, even a very good one, must undergo change in order to keep up with the hormone-driven rewiring of a woman’s brain during the years leading up to and including menopause. Not all marriages are able to survive these changes. Mine wasn’t, and nobody was more surprised about that than I. If this makes you want to hide your head in the sand, believe me, I do understand. But for the sake of being true to yourself and protecting your emotional and physical health in the second half of your life—likely a full forty years or more—then I submit to you that forging ahead and taking a good hard look at all aspects of your relationship (including some previously untouchable corners of your marriage) may be the only choice that will work in your best interest in the long run, physically, emotionally, and spiritually.

From the standpoint of physical health, for example, there is plenty of evidence to suggest that the increase in life-threatening illnesses after midlife, which cannot be accounted for by aging alone, is partly rooted in the stresses and unresolved relationship problems that simmered beneath the surface during the childbearing years of a woman’s life, then bubbled up and boiled over at perimenopause, only to be damped down in the name of maintaining the status quo. The health of your significant other is also at stake. Remaining in a relationship that was tailor-made for a couple of twentysomethings without making the necessary adjustments for who you both have become at midlife can be just as big a health risk for him as it is for you.

This is not to say that your only options are divorce or heart attack. Rather, in order to bring your relationship into alignment with your rewired brain, you and your significant other must be willing to take the time and spend the energy to resolve old issues and set new ground rules for the years that lie ahead. If you can do this, then your relationship will help you to thrive in the second half of your life. If one or both of you cannot or will not, then both health and happiness may be at risk if you stay together.

Preparing for Transformation

At midlife, more psychic energy becomes available to us than at any time since adolescence. If we strive to work in active partnership with that organic energy, trusting it to help us uncover the unconscious and self-destructive beliefs about ourselves and our unhealed hurts that have held us back from what we could become, then we will find that we have access to everything we need to reinvent ourselves as healthier, more resilient women, ready to move joyfully into the second half of our lives.

This process of transformation can only succeed, however, if we become proactive in two ways. First, we must be willing to take full responsibility for the problems in our lives. This is the most difficult step you will ever take, and the most liberating one. It takes great courage to admit our own contributions to the things that have gone wrong for us and to stop seeing ourselves simply as victims of someone or something outside of ourselves. After all, the person in the victim role tends to get all the sympathy and to assume the high road morally, which is appealing; none of us wants to feel like the bad guy. But even though taking the victim role may seem a good choice in the short run, this stance is ultimately devoid of any power to help us change, heal, grow, and move on to a more fulfilling and joyful life.

The second requirement for transformation is more difficult by far: we must be willing to feel the pain of loss and grieve for those parts of our lives that we are leaving behind. And that includes our fantasies of how our lives could have been different if only. Facing and feeling such loss is rarely easy, and that is why so many of us resist change in general and at midlife in particular. A part of us rationalizes, “Why rock the boat? I’m halfway finished with my life. Wouldn’t it just be easier to accept what I have rather than risk the unknown?”

The end of any significant relationship, or any major phase of our lives, even one that has made us unhappy or held us back from our full growth and fulfillment, feels like a death—pure and simple. To move past it, we have to feel the sadness of that loss and grieve fully for what might have been and now will never be.

And then we must pick ourselves up and move toward the unknown. All our deepest fears are likely to surface as we find ourselves facing the uncertainty of the future. During my own perimenopausal life changes, I would learn this in spades—much to my surprise.

By the time I was approaching menopause, I had worked wit

h scores of women who had gone through midlife “cleansings”; I had guided and counseled them as their children left home, their parents got sick, their marriages ended, their husbands fell ill or died, they themselves became ill, their jobs ended—in short, as they went through all the storms and crises of midlife. But I never thought I would face a crisis in my marriage. I had always felt somewhat smug, secure in my belief that I was married to the man of my dreams, the one with whom I would stay “till death do us part.”

Delirious Happiness and Shaking Knees

I will always remember the happiness of meeting and marrying my husband, a decision we made merely three months after we met. He was my surgical intern when I was a medical student at Dartmouth. He looked like a Greek god, and I was deeply flattered by his attention, especially since I wasn’t at all sure I had what it took to attract such a handsome man with an Ivy League, country-club background. Something deep within me was moved by him beyond all reason, beyond anything I’d ever felt before with any other boyfriend. For the first five years of our marriage my knees shook whenever I saw him. There wasn’t a force on this planet that could have talked me out of marrying him. I remember wanting to shout my love from the tops of tall buildings—an exuberance of feeling that was very uncharacteristic of the quiet, studious valedictorian of the Ellicottville Central School class of 1967.

He, however, was considerably less eager to display his feelings. I couldn’t help but notice during the years we were both immersed in our surgical training that my husband seemed uncomfortable relating to me when we were at work, and often appeared cold and distant when I’d try to show affection in that setting. This puzzled and hurt me, since I was always proud to introduce him to my patients when we happened to see each other outside of the operating room. But I told myself that this was because of the way he had been raised, and that with enough love and attention from me, he would become more responsive, more emotionally available.

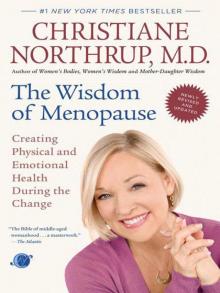

The Wisdom of Menopause

The Wisdom of Menopause